Anger is often misunderstood, particularly anger in children. Many adults perceive anger as a negative emotion that must be suppressed or avoided. However, modern research in psychology and neuroscience suggests that anger is not inherently bad. Instead, anger serves a vital function in human development (Boiger et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2018). As educators, teachers or parents of children or young people, we must shift our perspective from managing or eliminating anger to understanding and supporting children as they navigate their emotional landscapes.

Dr Lisa Feldman Barrett’s Theory of Constructed Emotion (Feldman Barrett., 2017a) challenges the traditional view that emotions are hardwired responses that everyone experiences in a universal way. Instead, she asserts that emotions are constructed experiences, shaped by a person’s physiological state, sensory input, past experiences, and present context. Anger, like all emotions, is not a simple reaction that we are at the mercy of, but a complex, context-dependent response to a situation where a need is unmet.

See Lisa’s website for more of her work here: https://lisafeldmanbarrett.com/

Anger is an emotion of action. Anger motivates us to address problems, set boundaries, and advocate for ourselves. In early childhood, anger is often the most simple and effective way for a child to express frustration, disappointment, or injustice. When a child becomes angry, they are not being ‘naughty’ or ‘difficult,’ they are experiencing an internal signal that something in their environment needs to change. When a child throws themselves to the floor in frustration or shouts in defiance, they are communicating a need in the best way they know how. Young children may not yet have the language or emotional regulation skills to articulate complex feelings, so they use their behaviour to express them instead. When we see a child ‘throwing a tantrum’ or ‘having a meltdown’ it can be so very difficult not to see this as a personal attack against us. We are trying our best to meet their needs, so when they respond with such violent emotions, it can very quickly trigger our own powerful emotions.

Rather than viewing outbursts as deliberate misbehaviour, we should ask ourselves:

"What is this child’s behaviour telling me about their unmet need?"

Or instead - What need is motivating this behaviour, and how can I support the child to meet it in a healthy way?

Perhaps they are overwhelmed by sensory input, frustrated by a challenging task, or struggling with social dynamics. Which need is creating this big stress response in them? At Phoenix Support for Educators, we recognise anger as a defence against empty Cups (see more about the Phoenix Cups® framework here), we can shift our response from punishment to guidance, helping children and young people to develop more effective ways to express their needs.

Imagine you are upset or angry about something that deeply matters to you. Your feelings are valid, and yet someone tells you to ‘calm down’, ‘stop overreacting’, or that ‘everything is fine’. Would you feel heard? Would your emotions instantly dissipate? Or would you feel dismissed, frustrated, and even more upset?

Children experience emotions just as intensely as adults. Perhaps even more so, as they have fewer coping strategies at their disposal. As we say in the Phoenix Cups framework, they’re still developing skills to fill their Cups. There’s another reason they experience emotions more intensely and it’s because they are what Dr Louise Porter calls ‘serial emoters’ - experiencing one emotion at a time... When we dismiss children's anger, we teach children that their emotions are not important or that they must suppress them to be acceptable. Instead of shutting down their feelings, we should acknowledge them.

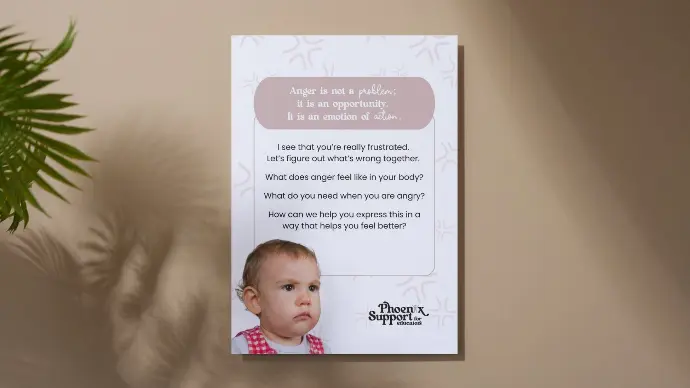

"I see that you’re really frustrated right now. Let’s figure out what’s wrong together."

The Problem with Colour-Coding Emotions

Many educational settings use colour-based emotional regulation charts, where emotions are assigned a colour. Anger is typically classed as red, which children and the world see as bad or negative, through to green states of being which include happiness and excitement. The idea of this sort of traffic-light system teaches children that we need to stop the red zone and move into the green zone. While well-intentioned, this can inadvertently reinforce the idea that some emotions are ‘bad’ and should be avoided, while others are ‘good’ and should be pursued.

But anger is not red, nor is it something to be feared. Anger is not a problem in itself; it is how we respond to anger that matters. The goal should not be to force a child from ‘red’ to ‘green’ but to help them develop the skills to navigate their emotions constructively. When a child is justifiably angry, our role is not to dismiss or suppress that feeling but to help them understand, express, and manage it in a healthy way.

Instead of categorising emotions as ‘good’ or ‘bad’, we can focus on building emotional literacy:

- What does anger feel like in your body?

- What do you need when you are angry?

- How can we help you express this in a way that helps you feel better?

This approach fosters emotional intelligence and self-awareness, skills that will benefit children throughout their lives. We need to understand emotion through the lens of construction rather than as hardwired, universal reactions. Anger, like all emotions, isn’t a fixed circuit in the brain waiting to be triggered — it's something we construct, moment to moment, based on our past experiences, concepts we've learned, and the sensory input we're interpreting (Feldman Barrett, 2017b).

When we treat anger — or any emotion — as something inherently ‘bad’ or needing suppression, we're missing a critical opportunity to teach children the skills of emotional granularity and regulation. If a child is consistently told to 'stop being angry', what they learn is not how to navigate the feeling, but that the feeling itself is unacceptable. This often leads to what Lisa would call conceptual impoverishment. They don’t develop a nuanced vocabulary or understanding of their inner world. And when you can’t name or understand what you're feeling, you can’t regulate it effectively either (Feldman Barrett, 2017a).

So yes, if we suppress or vilify anger, we’re not eliminating it — we’re simply pushing it into stress, anxiety, or misdirected aggression. Instead, we should be teaching children to construct different emotional meanings for their arousal and discomfort. This is not about dismissing anger but expanding the range of concepts they can use to interpret and act upon it. That’s the foundation of healthy emotional regulation.

Instead, our goal should be to equip children with the tools they need to handle strong emotions effectively.

- Acknowledge and validate emotions – “I see that you’re really angry right now. That’s okay. Let’s figure out what’s going on.”

- Model self-regulation – Demonstrate how you manage frustration in healthy ways, such as deep breathing, taking a break, or talking through feelings.

- Teach problem-solving skills – Guide children to find solutions when they are upset, such as using words instead of hitting or asking for help when they are frustrated.

- Create a safe emotional environment – Let children know that all feelings are welcome and that they will not be shamed for expressing them.

- Encourage self-awareness – Help children recognise how anger feels in their bodies and what helps them to feel better.

- Teach emotional granulation to children by giving them the words for specific feelings (like frustrated, annoyed, furious, irritated or overwhelmed instead of just "angry") through stories, games, and open conversations about emotions.

When raising, educating or caring for children and young people, we have a powerful opportunity to shape how children understand and manage their emotions. Instead of viewing anger as a behaviour that must be stopped, we can embrace it as a valuable and necessary part of human experience. Rather than focusing on calming a child down or moving them towards a ‘green’ emotional state, we should prioritise helping them develop the skills they need to navigate their emotions effectively.

When we allow space for anger, validate feelings, and teach self-regulation, we are giving children the emotional foundation they need for life. Healthy expression of our feelings leads to resilience, confidence, and emotional intelligence.

Anger is not a problem; it is an opportunity. Let’s ensure we respond to anger in a way that empowers children rather than silences them.

Download the Free Educator Prompt Poster

Please subscribe below to download a copy of the poster:

References

Boiger, M., Mesquita, B., Uchida, Y., & Feldman Barrett, L. (2013). Condoned or Condemned: The Situational Affordance of Anger and Shame in the United States and Japan. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(4), 540–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213478201

Feldman Barrett, L. (2017a). How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. Pan Macmillan.

Feldman Barrett, L. (2017b). The theory of constructed emotion: an active inference account of interoception and categorization, Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(1), 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsw154

Liu, C., Moore, G. A., Beekman, C., Pérez-Edgar, K. E., Leve, L. D., Shaw, D. S., Ganiban, J. M., Natsuaki, M. N., Reiss, D., & Neiderhiser, J. M. (2018). Developmental Patterns of Anger From Infancy to Middle Childhood Predict Problem Behaviors at Age 8. Developmental Psychology, 54(11), 2090–2100. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000589

Author: Briana Thorne